Tuesday, April 26, 2016

Knowing You Know Nothing

(From an episode of The Simpsons, set at the church ice cream social)

Lisa: “What flavors do you have?”

Rev. Lovejoy: “Well, chocolate, vanilla, strawberry, and our new Unitarian flavor ice cream.”

Lisa: “I’ll have that” (Rev hands her an empty bowl)

Lisa: “But there’s nothing in there.”

Rev: “Eeeexactly.”

We Unitarian Universalists are an interesting bunch. Some of us arrive here knowing we have the truth and things figured out; some of us believe we have the truth, but are open to mystery and wonder-revelation. Heck, even our fifth principle tells us that we are on a journey together to seek the truth in love. Those outside of Unitarian Universalism say we believe anything or we believe nothing. I’ve been thinking about how Unitarian Universalists may dismiss or scoff at things they cannot see, hear, and touch. How can we be so certain when we don’t know what we don’t know. I know you don’t know what you don’t know and I know that you know that that I don’t know what I don’t know. You know? There is mystery, indeed.

Let me tell you a story from my own life. I’ve shared with you that my early childhood was traumatic and my relationship with my mother was strained until her death. However, there are bits of my childhood where my mother is concerned that I cherish. In the evening I would often find my mother stretched out looking at the stars. We lived in the foothills of the Adirondack Mountains so you can imagine what the night sky might look like. Broad, open, and filled with stars. I would join my mother and stargaze with her. It was in those moments that my mother was calm, generous, and loving.

We talked about everything especially the mysteries of the universe. What was out there? What were the possibilities? We realized there was so much that we didn’t know about the universe and other mysteries. Those moments are seared in my mind as precious memory of my mother and a special time that we shared together. That is the why of experiencing mystery and wonder. So that we can have moments of awe that keep us connected with others, so that we can remember times of shared living, so that we can continue to be in awe of the universe, and so that we can share our enthusiasm for life and love and affirm a willingness to approach one another with an open heart, an open mind in ways that support mystery and awe.

The phrase "I know that I know nothing" or "I know one thing: that I know nothing", sometimes called the Socratic paradox, is a well-known saying that is derived from Plato's account of the Greek philosopher Socrates. The phrase is not one that Socrates himself is ever recorded as saying, and there is some disagreement about whether it accurately represents a Socratic view. If it were not for Plato we might not know a lot of what Socrates said. Plato investigated Socrates's explanation of that aspect of his philosophy often termed "the Socratic Paradox." Socrates believed that we all seek what we think is most genuinely in our own interest. (Obviously, short-term pleasure or success is often not in our best interest. The long-term effect on the soul is, however.)

On the one hand, if we act with knowledge, then we will obtain what is good for our soul because "knowledge" implies certainty in results. On the other hand, if the consequences of our action turn out not to be what is good for our soul (and hence what is genuinely not in our self-interest), then we had to have acted from ignorance because we were unable to achieve what we desired. In a sense, then, for Socrates, there is no ethical good or evil in things in the world — things are what they are. Instead, "knowledge" is considered to be materially equivalent to what is "good," "excellence," and "ignorance" is considered to be materially equivalent to "evil" or what is "harmful to our soul." If harm happens to us, then, at some point, we had to have acted with a lack of knowledge. In this manner, Socrates concludes, what to many persons seems paradoxical, that we are "morally responsible" for obtaining all the knowledge we can. In this sense, ignorance is no excuse.

Let’s go back to the paradox. The meaning of the word "paradox" itself.. the word’s origin is Greek.. the prefix ‘para’ means beyond and dox from the Greek meaning opinion or belief. So the literal meaning of "paradox" is "beyond belief". The best word for something beyond belief, it seems to me, is “mystery”. In our quest to be part of the greater, unseen, unliteral world of creative power and mystery, we must consider faith and mystery. As Unitarian Universalists we affirm and promote seven principles, which we hold as strong values and moral guides. We live out those principles within a “living tradition” of wisdom and spirituality, drawn from sources as diverse as science, poetry, scripture, and personal experience. There are six sources and we will focus on the first today which is “Direct experience of that transcending mystery and wonder, affirmed in all cultures, which moves us to a renewal of the spirit and an openness to the forces which create and uphold life.” That source instructs us to have an openness to the forces that create and uphold life and to the forces that take life.

One of our preeminent theologians of the 20th century, James Luther Adams, said it like this: “Religious liberalism depends on the principle that ‘revelation’ is continuous.’” It means that the only kind of bible a Unitarian Universalist could believe in is a Wikipedia-type bible. It means that, when Unitarian Universalists read the Hebrew bible and the Christian bible in a way that is faithful to our theological tradition, we never read it literally and in a way that assumes the ancient message — the meaning of it — is frozen in the amber of time. Always, we are finding ways to value the old insights in the context of their time, and to evolve the old insights so that they can serve new understandings and new needs. We believe in evolution.

The hymn that we sang, Light of Ages and of Nations #189, is set to an older hymn tune. The words were written in 1860 by the Unitarian minister Samuel Longfellow, younger brother of the more famous Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, the poet. It’s believed to be one of the earliest hymns to fully recognize non-Christian traditions. The expression in verse three is “revelation is not sealed.” But really the entire hymn is a testimony to the Unitarian Universalist beliefs that there is truth in all religions and that the potential to know truth exists in all people, of all times and places, including today, and here. The first part is about religious diversity. In our view, revelation was never restricted to one religion.

Especially today, in the present climate of intolerance, it is a powerful message. We are not new to interfaith understanding. We have a century and a half of experience from which to draw in understanding and working with our brothers and sisters of other faiths. We have an historic appreciation, written in our souls’ deep pages (as the hymn says), of the truth of their religion for them. We know that it is as true – no more, no less – for them as ours is for us. You ask what gives Unitarian Universalism power? There is power in our belief that the possibility of revelation was 1) not ever restricted to one religious group and 2) continues to be as possible as ever. We don’t know what we don’t know and should be open to the mystery.

The second part is that revelation is still possible. Ours is a “living tradition,” we like to say. It has evolved over time and will continue to do so, in large part because it is not tied to an ancient scripture or institutional creed. We do not hold onto the literal meaning of scriptures that originated in a historic context different than ours, defined by the customs and values of their (ancient) times. While we can, and do, find meaning in scriptures for our own times, the first source from which we draw is our own direct experience of that transcending mystery and wonder that moves us to a renewal of the spirit and an openness to the forces that create and uphold life. We rely on our experience to know the truth, which will set us free. I don’t know what I don’t know. Hey, I play it safe. I have no expectations for the afterlife but if I do arrive at a pearly gates rather than plead the fifth I will get in by the skin of my nose having been open to revelation and mystery.

Sometimes, our experience causes us to challenge our own faith principles. Take for example Rev. Bill Schulz, executive director of the Unitarian Universalist Service Committee. His experience encountering evil, advocating for victims of torture and opposing the death penalty, caused him to doubt the first principle that Unitarian Universalist congregations covenant to affirm and promote: the inherent worth and dignity of every person. He said in a 2006 lecture to UU ministers, “I don’t buy that anymore. I have fought tirelessly against the death penalty in this country. I have visited death rows, spoken frequently with condemned prisoners. Some of them have acknowledged their crimes and altered their hearts. Others of them are truly innocent. Many of them are mentally ill. And some of them are vicious, dangerous killers. I oppose the death penalty not because I believe that every one of those lives carries inherent worth… I oppose the death penalty because I can’t be sure which of them falls into which category and because the use of executions by the state diminishes my own dignity and that of every other citizen in whose name it is enforced. I need, in other words, to assign the occupants of death row worth and dignity in order to preserve my own. But I find no such characteristics inherent in either them or me.” So is the worth and dignity of every person inherent? “No,” he says. “Each of us has to be assigned worth — it does not come automatically — and taught to behave with dignity…” That we must draw on our own experience, and can question even our own principles, is a source of power. It’s not easy, but it engages and energizes us and therefore enables us to take action on behalf of our principles, to do the work of love and justice in this world. It gives us power.

Ongoing revelation, questioning, transformation… with so much change, what lends stability to our faith tradition, which we sometimes even call a “movement” rather than a “denomination,”? The word “religion” means “to bind together.” By what are we bound? We are not bound by creeds, but by covenants. We are bound by promises we make about how we will be together. We call them covenants, a Biblical word. Our members covenant with new members, and congregations covenant with each other, as member congregations of the Unitarian Universalist Association. So, grounded in covenants, empowered by our belief in ongoing revelation, what is it all for? Is it all just for us, individually and collectively, or are we empowered for something larger than ourselves, this congregation, this movement? One of the joys of belonging to a free faith is the right to wrangle with questions like these. Human beings have asked themselves such questions over and over again, and, not surprisingly, have come up with different answers. We can only invite one another to ask the questions because we believe that faith is a journey and “revelation is not sealed.” Change is constant. We honor the great mystery as one of our sources of our faith. We don’t know what we don’t know and must be open to that.

The author Rabi Michael Lerner is a political activist and rabbi at a synagogue in Berkeley, Ca. He is editor of a progressive magazine focused on social and religious activism. He is chair of the interfaith Network of Spiritual Progressives, rabbi of and author of eleven books, including the national best-seller The Left Hand of God: Taking Back our Country From the Religious Right. His sentences, “It is the reality of human experience that at our core we respond to the universe with a sense of awe and wonder at creation.” And “We are dazzled by the incomprehensible fact of being itself.” are to my mind the deep thoughts behind our first source. We cannot not seek for the sacred, the mystery, and the wonder which moves us to renew our spirit and opens us to the forces that uphold life. It is part of our DNA, part of our being; it is the essence of our humanness.

So we look and we wonder and we search and we argue for and against, and we believe, and we don’t, and we change our mind, but the reality, as Rabbi Michael Lerner reminded us, is that at the core of the human experience we respond to the universe with a sense of awe and wonder and we are amazed by the incomprehensible fact of all of existence. Exploring your thoughts and beliefs, your experiences your ideas is what can deepen your spiritual self.

Here are some thoughts I would like to leave you with: the universe is richer than we can imagine; life is more mysterious than we can find answers to; human nature will always want to know the why, the what and the how. Being a religious, spiritual person is the how. Let’s together find the fire in our faith and use it to light a path to a future, more just, more loving world.

May it be so.

Knowing You Know Nothing, a sermon delivered at 1stUUPB by the Rev. CJ McGregor on April 24, 2016.

Saturday, April 23, 2016

Changing of the Guard

President’s Bully Pulpit #12

April, 2016

To all the members and friends of 1stUUPB:

Thank you for giving me the opportunity to serve as your president during 2015-16. It has been an honor and a privilege to lead our Congregation throughout this church year.

I want to give special thanks to the members of the Board of Trustees, the chairs of committees, and the members of Team 7 Stewardship Campaign, for all the wonderful volunteer work they have done during my presidency. I am especially indebted to staff member Barbara Hatzfeld, our church office administrator, for her assistance and cooperation.

There is a person upon whom I have relied more than any other. She is a very hard working and highly capable individual. She has served as the temporary recorder of Board minutes. She has been a leader on Team 7, the Stewardship Campaign Planning Committee. And she is the principal facilitator of our popular Dine Around fund raisers. I am speaking of my life partner and friend of 62 years, fellow Baltimorean and Forest Park High School graduate of February ’57, Phyllis Levin. Thank you Phyllis for all your efforts and for all that you have helped accomplished for our Congregation. 1stUUPB could not have a better friend. Nor could I.

Beginning on May 1st, Phyllis and I will be scaling back our participation in church activities. We will be Friends of the church and visit on occasion to attend services and Teaching Thursday programs.

I wish my successor in the presidency, Paul Ward, all the best for the coming year, and pledge that I will continue to take an interest in Congregational life going forward. Phyllis and I hope we will have lots of opportunities to socialize with our church friends. We are heading to Alaska in June for a new travel adventure.

Andrew Kahn

April, 2016

To all the members and friends of 1stUUPB:

Thank you for giving me the opportunity to serve as your president during 2015-16. It has been an honor and a privilege to lead our Congregation throughout this church year.

I want to give special thanks to the members of the Board of Trustees, the chairs of committees, and the members of Team 7 Stewardship Campaign, for all the wonderful volunteer work they have done during my presidency. I am especially indebted to staff member Barbara Hatzfeld, our church office administrator, for her assistance and cooperation.

There is a person upon whom I have relied more than any other. She is a very hard working and highly capable individual. She has served as the temporary recorder of Board minutes. She has been a leader on Team 7, the Stewardship Campaign Planning Committee. And she is the principal facilitator of our popular Dine Around fund raisers. I am speaking of my life partner and friend of 62 years, fellow Baltimorean and Forest Park High School graduate of February ’57, Phyllis Levin. Thank you Phyllis for all your efforts and for all that you have helped accomplished for our Congregation. 1stUUPB could not have a better friend. Nor could I.

Beginning on May 1st, Phyllis and I will be scaling back our participation in church activities. We will be Friends of the church and visit on occasion to attend services and Teaching Thursday programs.

I wish my successor in the presidency, Paul Ward, all the best for the coming year, and pledge that I will continue to take an interest in Congregational life going forward. Phyllis and I hope we will have lots of opportunities to socialize with our church friends. We are heading to Alaska in June for a new travel adventure.

Andrew Kahn

Monday, April 4, 2016

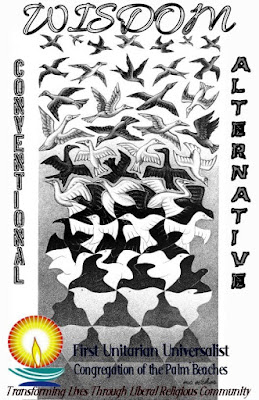

Two Kinds of Wisdom

A priest and a nun were lost in a snowstorm. After a while, they came upon a small cabin. Being exhausted, they prepared to go to sleep. There was a stack of blankets in the corner and a sleeping bag on the floor but only one bed. Being a gentleman, the priest said, “Sister, you sleep on the bed. I’ll sleep on the floor in the sleeping bag.”

Just as he got zipped up in the bag and was beginning to fall asleep, the nun said, “Father, I’m cold.” He unzipped the sleeping bag, got up, got a blanket and put it on her.

Once again, he got into the sleeping bag, zipped it up and started to drift off to sleep when the nun once again said, “Father, I’m still very cold.” He unzipped the bag, got up again, put another blanket on her and got into his sleeping bag once again.

Just as his eyes closed, she said, “Father, I’m sooooo cold.” This time, he remained there and said, “Sister, I have an idea. We’re out here in the wilderness where no one will ever know what happened. Let’s pretend we’re married.” The nun purred, “That’s fine by me.”

To which the priest yelled back, “Get up and get your own stupid blanket!”

There are two types of wisdom. The most common type of wisdom is conventional wisdom. This is the mainstream wisdom of a culture, "what everybody knows," a culture's understandings about what is real and how to live. The second type is an unconventional and alternative wisdom. That wisdom questions and undermines conventional wisdom and speaks of another way. Now conventional wisdom in the story of the nun and the priest tells us the appropriate relationship between nun and priest and the familiar perception of married couples.

What are we to learn from conventional wisdom and as Unitarian Universalists should we challenge it? I turn to the work of Biblical scholar Marcus Borg for help. Much of what I ask you to consider today is drawn from his book Meeting Jesus Again for the First Time. Borg was a leading liberal scholar and theologian. He was the leading scholar of the historical Jesus. That is, he attempts to reconstruct the life of a man, not a deity, using critical historical methods. Borg’s understanding was not rooted in dogma but spiritual challenge, compassion, community, and justice. That sounds very Unitarian Universalist to me. I read his book as suggested by a member of the Congregation and it gives us a lens through which we can look at wisdom today.

Borg uses the historical Jesus to name two types of wisdom. Conventional wisdom is taken-for-granted knowledge about the way things are and how to live. It’s what everyone tends to know through our socialization process and growing up. It gives us guidance on how to live, including basic etiquette and larger images of the good life, perhaps like the American Dream in this country. Generally, it teaches that if you work hard, you will succeed, and you will get what you deserve. Conventional wisdom becomes internalized and is the internal cop and the internal judge of what society generally thinks is right and wrong and should be rewarded or punished.

And Radical, unconventional Wisdom leads to an entirely new way of living, a new ethic and social vision in which one turns the other cheek, loves not only one’s neighbor, but also one’s enemy, judges not lest one be judged oneself, and does to others only what you would have them do to you. Radical, unconventional Wisdom transforms our personal sense of identity, moving us beyond what our cultural conventions say we are and liberating us from the anxieties and preoccupations that mark so much of our lives. It is a source of courage as well as endurance.

We know that conventional wisdom isn’t always the truth. Take, for example, the American dream I just described seconds ago that is conventional wisdom. It is not based in reality. If it were there wouldn’t be such disparity between the classes, racial inequalities and divides, American families who are hungry and homeless, and a government that risks the well-being of its citizens. If ideas are wrong, why do we persist in believing them and continuing the same action? The reason may be that, after we have heard something a number of times, it becomes a part of our belief system, or to put it differently, it becomes a part of the frame through which we assess a situation and act. It becomes our reality. The mind doesn't know the difference between that which is real and that which is not. Our perception is our reality.

In my own life I’ve had to defy conventional wisdom to maintain an emotionally healthy family. When Richard and I adopted our children we knew how we wanted to raise them. We knew what kind of home we wanted to build and we had hopes. We knew we wanted to raise our children the conventional way. Because our children were so challenging we needed to lose our identities of the parents we wanted to be and defy conventional wisdom and become the parents we needed to be. It was difficult and created a huge sense of loss. But because we chose alternative wisdom, radical wisdom, our children are successful today and Richard and I are still in relationship. Had we clung to the conventional. we and our children would now be at risk as adults and our relationship would be terribly strained. We released ourselves from the anxieties of conventional wisdom, wisdom that held no truth for our family.

Conventional wisdom, according to Borg, creates the world in which we live. It provides guidance about what is socially acceptable and, in the West, comforts us with the belief that we will be rewarded for hard work. Rewards and punishment are a part of our conventional wisdom. Work hard in school and you will succeed. Strive in business and you will do well. Keep a perfect house and your family will be happy.

The problem is that there’s a rather harsh backside to this wisdom. If you aren’t succeeding you must have done something wrong. If you don’t prosper than you aren’t worthy. If your family has problems you must be using the wrong dish detergent. The world of our conventional wisdom is a realm in which we measure ourselves against others. Compared to others, how attractive, prosperous, intelligent and popular are we? It is a world in which there is plentiful stress and a multitude of reasons to become disillusioned.

You see, as Unitarian Universalists we are called to redefine conventional wisdom and employ unconventional, or radical, wisdom. Wisdom that brings us closer to our values of love, compassion, freedom, and reason. What Marcus Borg helps us to see, using the historical Jesus, is that living a life engaged in alternative or radical wisdom has several dimensions: a passion for social justice, understanding the importance of life in community, and limited concern about the afterlife in favor of a transformed wisdom that requires challenging the dominating systems created and maintained by the rich and powerful to serve their own interests. Compassion as a virtue for individuals is partially blind unless it’s married to an understanding that much of the world’s misery flows from systemic injustice and then having a willingness to work to change it. He presents Jesus as a man whose spiritual experiences led him to see beyond the conventional wisdom of his day and the boundaries that it created between people. The model life he associates with this image of Jesus is a continuous journey of transformation -- not arriving at a new conventional wisdom and a new set of rules, but always challenging our conventional, rule-based way of thinking. These are exactly some of the principles to we commit to in our Unitarian Universalist faith.

Think of an issue in your life or in the world today. What does conventional wisdom say about it? Conventional wisdom becomes conventional because it has an inherent truth to it, or at least it once did. In our rush to adopt the shorthand of business, we can easily miss the subtleties and nuances that should give pause, and thought, to what we are doing. Sometimes things get said without much substance and then these things become conventional wisdom that we all go along with even though the reasoning may be flawed in the first place. Even when misguided actions are pointed out to people they often do not or cannot hear what is being said because they are doing something that "everyone" knows is right because it is "conventional wisdom". What conventional wisdom have you seen do more harm than good? What have you done about it?

How should we listen to Wisdom? We should go out of this church trying to live and move and have our being in Wisdom as the Spirit of life that helps us to love, both in deed and in truth. That requires a radical social ethic which is willing to work against systemic injustice in the world. We should try to stop worrying and fearing and being anxious, for that closes our eyes and ears to the abundance of life all around us here and now that we can savor and appreciate, even as the world is yet to be fully transformed and redeemed.

Let me share with you some unconventional wisdom:

May it be so.

Two Kinds of Wisdom, a sermon delivered by the Rev CJ McGregor at 1stUUPB, April 3, 2016.

Just as he got zipped up in the bag and was beginning to fall asleep, the nun said, “Father, I’m cold.” He unzipped the sleeping bag, got up, got a blanket and put it on her.

Once again, he got into the sleeping bag, zipped it up and started to drift off to sleep when the nun once again said, “Father, I’m still very cold.” He unzipped the bag, got up again, put another blanket on her and got into his sleeping bag once again.

Just as his eyes closed, she said, “Father, I’m sooooo cold.” This time, he remained there and said, “Sister, I have an idea. We’re out here in the wilderness where no one will ever know what happened. Let’s pretend we’re married.” The nun purred, “That’s fine by me.”

To which the priest yelled back, “Get up and get your own stupid blanket!”

There are two types of wisdom. The most common type of wisdom is conventional wisdom. This is the mainstream wisdom of a culture, "what everybody knows," a culture's understandings about what is real and how to live. The second type is an unconventional and alternative wisdom. That wisdom questions and undermines conventional wisdom and speaks of another way. Now conventional wisdom in the story of the nun and the priest tells us the appropriate relationship between nun and priest and the familiar perception of married couples.

What are we to learn from conventional wisdom and as Unitarian Universalists should we challenge it? I turn to the work of Biblical scholar Marcus Borg for help. Much of what I ask you to consider today is drawn from his book Meeting Jesus Again for the First Time. Borg was a leading liberal scholar and theologian. He was the leading scholar of the historical Jesus. That is, he attempts to reconstruct the life of a man, not a deity, using critical historical methods. Borg’s understanding was not rooted in dogma but spiritual challenge, compassion, community, and justice. That sounds very Unitarian Universalist to me. I read his book as suggested by a member of the Congregation and it gives us a lens through which we can look at wisdom today.

Borg uses the historical Jesus to name two types of wisdom. Conventional wisdom is taken-for-granted knowledge about the way things are and how to live. It’s what everyone tends to know through our socialization process and growing up. It gives us guidance on how to live, including basic etiquette and larger images of the good life, perhaps like the American Dream in this country. Generally, it teaches that if you work hard, you will succeed, and you will get what you deserve. Conventional wisdom becomes internalized and is the internal cop and the internal judge of what society generally thinks is right and wrong and should be rewarded or punished.

And Radical, unconventional Wisdom leads to an entirely new way of living, a new ethic and social vision in which one turns the other cheek, loves not only one’s neighbor, but also one’s enemy, judges not lest one be judged oneself, and does to others only what you would have them do to you. Radical, unconventional Wisdom transforms our personal sense of identity, moving us beyond what our cultural conventions say we are and liberating us from the anxieties and preoccupations that mark so much of our lives. It is a source of courage as well as endurance.

We know that conventional wisdom isn’t always the truth. Take, for example, the American dream I just described seconds ago that is conventional wisdom. It is not based in reality. If it were there wouldn’t be such disparity between the classes, racial inequalities and divides, American families who are hungry and homeless, and a government that risks the well-being of its citizens. If ideas are wrong, why do we persist in believing them and continuing the same action? The reason may be that, after we have heard something a number of times, it becomes a part of our belief system, or to put it differently, it becomes a part of the frame through which we assess a situation and act. It becomes our reality. The mind doesn't know the difference between that which is real and that which is not. Our perception is our reality.

In my own life I’ve had to defy conventional wisdom to maintain an emotionally healthy family. When Richard and I adopted our children we knew how we wanted to raise them. We knew what kind of home we wanted to build and we had hopes. We knew we wanted to raise our children the conventional way. Because our children were so challenging we needed to lose our identities of the parents we wanted to be and defy conventional wisdom and become the parents we needed to be. It was difficult and created a huge sense of loss. But because we chose alternative wisdom, radical wisdom, our children are successful today and Richard and I are still in relationship. Had we clung to the conventional. we and our children would now be at risk as adults and our relationship would be terribly strained. We released ourselves from the anxieties of conventional wisdom, wisdom that held no truth for our family.

Conventional wisdom, according to Borg, creates the world in which we live. It provides guidance about what is socially acceptable and, in the West, comforts us with the belief that we will be rewarded for hard work. Rewards and punishment are a part of our conventional wisdom. Work hard in school and you will succeed. Strive in business and you will do well. Keep a perfect house and your family will be happy.

The problem is that there’s a rather harsh backside to this wisdom. If you aren’t succeeding you must have done something wrong. If you don’t prosper than you aren’t worthy. If your family has problems you must be using the wrong dish detergent. The world of our conventional wisdom is a realm in which we measure ourselves against others. Compared to others, how attractive, prosperous, intelligent and popular are we? It is a world in which there is plentiful stress and a multitude of reasons to become disillusioned.

You see, as Unitarian Universalists we are called to redefine conventional wisdom and employ unconventional, or radical, wisdom. Wisdom that brings us closer to our values of love, compassion, freedom, and reason. What Marcus Borg helps us to see, using the historical Jesus, is that living a life engaged in alternative or radical wisdom has several dimensions: a passion for social justice, understanding the importance of life in community, and limited concern about the afterlife in favor of a transformed wisdom that requires challenging the dominating systems created and maintained by the rich and powerful to serve their own interests. Compassion as a virtue for individuals is partially blind unless it’s married to an understanding that much of the world’s misery flows from systemic injustice and then having a willingness to work to change it. He presents Jesus as a man whose spiritual experiences led him to see beyond the conventional wisdom of his day and the boundaries that it created between people. The model life he associates with this image of Jesus is a continuous journey of transformation -- not arriving at a new conventional wisdom and a new set of rules, but always challenging our conventional, rule-based way of thinking. These are exactly some of the principles to we commit to in our Unitarian Universalist faith.

Think of an issue in your life or in the world today. What does conventional wisdom say about it? Conventional wisdom becomes conventional because it has an inherent truth to it, or at least it once did. In our rush to adopt the shorthand of business, we can easily miss the subtleties and nuances that should give pause, and thought, to what we are doing. Sometimes things get said without much substance and then these things become conventional wisdom that we all go along with even though the reasoning may be flawed in the first place. Even when misguided actions are pointed out to people they often do not or cannot hear what is being said because they are doing something that "everyone" knows is right because it is "conventional wisdom". What conventional wisdom have you seen do more harm than good? What have you done about it?

How should we listen to Wisdom? We should go out of this church trying to live and move and have our being in Wisdom as the Spirit of life that helps us to love, both in deed and in truth. That requires a radical social ethic which is willing to work against systemic injustice in the world. We should try to stop worrying and fearing and being anxious, for that closes our eyes and ears to the abundance of life all around us here and now that we can savor and appreciate, even as the world is yet to be fully transformed and redeemed.

Let me share with you some unconventional wisdom:

- Before you criticize someone, you should walk a mile in their shoes. That way, when you criticize them, you're a mile away and you have their shoes.

- Give a man a fish and he will eat for a day. Teach him how to fish and he will sit in a boat and drink beer all day.

- If you lend someone $20 and never see that person again, it was probably worth it.

- If at first you don't succeed, skydiving is not for you.

- Do not walk behind me, for I may not lead. Do not walk ahead of me, for I may not follow. Do not walk beside me, either; just leave me the heck alone.

- It's always darkest before dawn. So if you're going to steal your neighbor's newspaper that's the time to do it.

- Don't be irreplaceable; if you can't be replaced, you can't be promoted.

- Give a man the fire and you'll keep him warm for one day. Set the man on fire -- and you'll keep him warm for the rest of his life.

- No one is listening until you make a mistake.

- Always remember you're unique, just like everyone else.

- It may be that your sole purpose in life is simply to serve as a warning to others.

- It is far more impressive when others discover your good qualities without your help. If you tell the truth, you don't have to remember anything.

- Some days you are the bug, some days you are the windshield.

- Good judgement comes from bad experience, and a lot of that comes from bad judgement.

- There are two theories to arguing with women. Neither one works.

- Generally speaking, you aren't learning much when your mouth is moving.

- Never miss a good chance to shut up.

- Experience is something you don't get until just after you need it.

May it be so.

Two Kinds of Wisdom, a sermon delivered by the Rev CJ McGregor at 1stUUPB, April 3, 2016.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)